chemical warfare agents

|

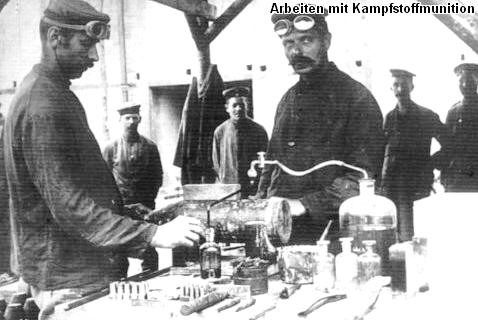

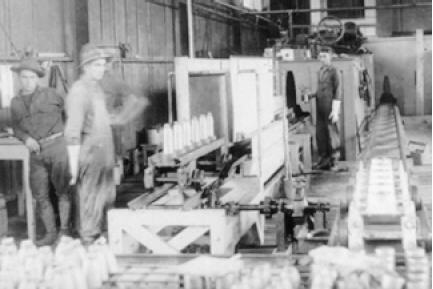

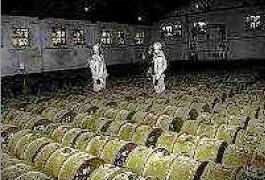

In this group there are poisons used by the army in order to kill, or permanently injure the enemy. Usage of such substances is prohibited, while manufacturing and storage restricted by international agreements. However, these restrictions do not apply to waste created during weapons production. Residues and byproducts are usually placed under the water (seas, lakes) or buried in the ground. It is estimated that the global inventory of combat poisons released into the environment would show more than one million tonnes. Due to the extremely hazardous and diversified properties of these waste, there is a lack of organized manner in which neutralization could takes place and storage locations are kept confidential. The largest quantity of such waste belong to the following groups:

Ways of localization and neutralization of chemical weapons are strongly related to types and configurations of this armament. The chemical toxins used to eliminate the enemy manpower shall be designed in such way that:

There are several patterns for application of chemical weapons. Each pattern requires different preparations of poisons.

Attacker prepares chemical toxins capable to affect targets located at the considerable distance. Distance must be large enough, so attacker remains without any exposure to the poison he spread. Poisons are carried by missile warheads, artillery shells and air bombs. The main objective is to create chaos within enemy’s territory, therefore typically, the density of the dispersed poisons is minimal. Panic among unprepared people (civilians or military personnel) ensues. This in turn disorganizes and disrupts emergency response services. Defender strengthens its line of defense, preparing and mounting chemical landmines firewalls. Such firewalls are in some cases ready to release even larger quantities of poisons. The task is to complete elimination or at least exhaustion of the opponents‘ troops and tactical military units. This of course is expected by the striker, therefore he tries to overpower enemy’s capacity by using more chemical warfare. Resulting vicious circle leads to premeditated planning and escalating use of new extremely strong toxic chemicals, possessing long term environmental stability, persistence and resistance to neutralization.

Strategic as well as tactical use of chemical weapons, requires long distance transportation of deadly cargo. This distance may vary and has to be determined by the user in order to not expose its own military forces. Small area can be successfully attacked by aircrafts used for pesticides spraying. Task is complicated - relatively small amount of toxins should cause massive destruction of enemy troops, but at the same time, the same chemicals should become quickly harmless and easy to neutralize by the troops overtaking the battleground.

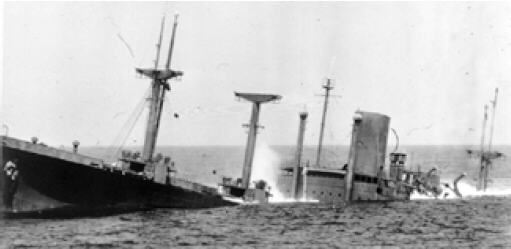

In order to exterminate large groups of people, poison must be highly effective, easy to spray and able to react quickly with water during neutralization.. This ensures minimal exposure for operators who damp poison into the gas chambers; they do not have to be concerned about traces of left-over deadly compounds. Terrorists plan use of poisons in contained spaces in order to kill or incapacitate maximum number of people with minimum amount of substance. However, additionally, such actions are designed to disorganize response of emergency teams as well; therefore selected poisons, would have rather long lasting chemical stability in this case. All the above, points to a little-known extra environmental problems. The multitude of ways how poisons can be utilized and applied, requires that producers must constantly modify toxic physicochemical properties of the active substances. Containers, unexploded bombs, mines and shells found in the environment must be analyzed not only for their main deadly content, but for additional components and by-products created during the chemical syntheses. Ultimately it is necessary to identify all components that have been used during the synthesis of particular poison. It is worth to observe , that in most of cases manufacturers of chemical poisons were not under any obligation to ordering party, to care and pay attention for environmental wellbeing. Consequently additional components and reagents selected for synthetic processes belonged to non-degradable organic toxins. Efforts to eliminate poisons from the combat environment get often complicated, because the presence of still not detonated explosives. Abandoned, useless armament remaining after the conflict, contains unexploded devices equipped with active igniters. Shells slowly corrode and poisonous substances sometimes penetrate explosives, what is the cause of chemical instability inside the shells. Therefore, the risk assessment for cleaning work must be extremely detailed. Possibilities of toxic shock as well as potential risk of direct explosion are extremely high. All this has to be taken under consideration before special forces decide to remove or dig out abandoned weapons. Without the doubt, neutralization of chemical weapons belong to the most dangerous and most expensive duties. This one fact alone is just enough to keep information (or at least to try) about the existence of such waste as a secret. It is not that difficult task - responsible institutions usually belong to military structures, where long tradition of maintaining the secrecy of possessing chemical weapons is widely approved and accepted. This type of weapons were always the most closely protected resources of any army. It would be highly inappropriate, should public and civilians recognize and perceive top military officials as treacherous poisoners.

|